The inflation rate was over 11 per cent last Autumn; in the mid-Seventies it surpassed 25 per cent. You would want to be protected against this rotting of your money, especially if you were a pensioner.

Last month I explained how the Government’s choice and operation of inflation indices for State benefits doesn’t work. Now I want to show how, even if the right index was used for annual increases, you would still lose out heavily.

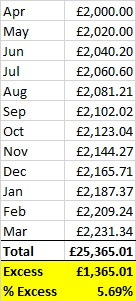

Let’s model the effects of inflation over a financial year, assuming initial living expenses of £2,000 a month and price rises of 1 per cent each month, compound:

By the time next April rolls around, your monthly outgoings are nearly 12 per cent higher. You may have budgeted for £24,000 a year, but the cumulative effect of inflation has required you to find an extra £1,365!

In practice the UK system is even worse - the inflation adjustment is based not on March (£2,231 in the above example) but on the previous September (£2,102, ditto), so you are already starting the new year six months behind the line. (For those thinking about the ‘Triple Lock,’ the NAEI figures used are even more out of date.)

If I were in charge of the CPI index and a cynic, I would lean on traders to rein in their prices in September; and revise the ‘basket of goods and services’ to come out with a minimised figure; but surely this never happens.

Nevertheless, honestly and accurately calculated or not, the annual update arrangement means you won’t get back last year’s shortfall and the losses will build up relentessly. At the rate illustrated, you would be short-changed overall by a whole year’s income during your expected period of retirement.

Now the damage is less if inflation is lower, more if higher; but the general principle applies and clearly it would be best if there were no inflation at all.

Those in work may counteract the effects by charging more for their work, though that’s not always possible. In addition or alternatively, they can switch to cheaper options (note the rise of discount supermarkets), cut back or cut down on luxuries.

But for claimants who are entirely reliant on their benefits, income is already low and then the squeeze is on. Enter the short-term lenders with their high interest rates, ultimately making matters worse; and at Christmas the ‘precariat’ buy food and presents on tick now and forget about tomorrow (which, however, will not forget about them.)

Judging by events in our own lifetime, we could easily imagine that inflation is inevitable and the defences against it have always been in place. Not so; but more on that later.

Let’s finish by recognising that inflation is a threat to the vulnerable, a disincentive to prudence and the enemy of personal freedom.