Time for a new US Constitution?

Many people seem to think that if the system can fix Trump that will fix the problem.

Absolutely not. Trump could never have been elected without a deep disturbance among the people, a submarine quake that unleashed the tsunami of 2016. Read what Albert Goldman says here and replace ‘the Beatles’, ‘they’ and ‘pop star’ with ‘Trump’, ‘he’ and ‘populist politician’:

Though it is customary to talk about what [the Beatles] contributed to contemporary consciousness, the truth is that the public imposed its fancies on [the Beatles] far more successfully than [they] could ever impart any idea to the world. This is the ironic fate of the [pop star]. Not so much a communicator or creator as a trigger or target for mass hysteria, the [pop star] finds his greatest gift is his ability to arouse the collective unconscious; but once he releases this mighty torrent of mental and emotional energy, he is seized and controlled by it so completely that he comes to feel like its slave.

The tectonic stresses that launched Trump’s surfboard onto a freak wave have been building from the foundation of the Republic - more correctly, the second Republic of 1791. Even then, there was a tension between the Federalists who wanted more concentration of wealth and power, and the Jeffersonian Democratic-Republicans who favoured decentralisation. The US might have progressed further and earlier towards a strong national government but the Louisiana Purchase of 1803 nearly doubled US territory and Jefferson’s 1804 landslide re-election stymied his opponents’ ‘last great hope -- that the New England states would secede and form a Federalist nation.’

If a second Republic, why not a third? Writing in 1816, Jefferson noted how already the political establishment increasingly appointed their friends to public office, without reference to the will of the people - the ‘mother principle.’ He suggested that once half those who had voted for the last Constitution had died, it was time for a fresh one to reflect the wishes of the living; ‘the dead have no rights.’

Yet who are ‘the people’? So much has changed over the centuries.

Take voter eligibility. In 1787, says this writer, only 20-25 per cent of the adult (aged over 21) population could vote: largely, white male property-owners and/or taxpayers; not slaves or ‘Indians’, nor (generally) women, Catholics, Jews or Quakers. Now, there are calls for the franchise to be extended even to non-citizens of the US; in January this year, New York City granted it to 800,000 such for municipal elections.

An electorate composed of those who own their own farms or other property, and who are used to solving financial, administrative and employment problems in their daily dealings, is likely to support one kind of government; a set of voters who can be bribed with promises of benefits from public funds, another.

Pre-industrial America has gone. Few people are completely independent of anything the State can do for them, and those - the millionaires and billionaires - are in a much better position to influence legislators than the miserable common voter. The result is a skewing of the economy, politics and taxation to reflect the wishes of an elite, who in their own way have become pensioners of the State. As Jefferson said:

I am not among those who fear the people. They, and not the rich, are our dependence for continued freedom. And to preserve their independence, we must not let our rulers load us with perpetual debt. We must make our election between economy and liberty, or profusion and servitude. […] Private fortunes are destroyed by public as well as by private extravagance. […] And the fore horse of this frightful team is public debt. Taxation follows that, and in its train wretchedness and oppression.

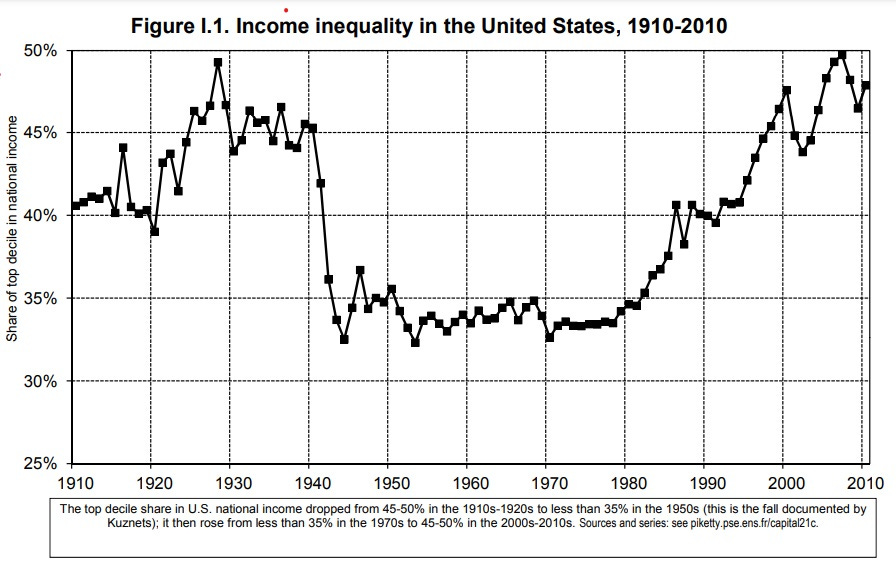

Taxation is not as heavy as he predicted - not 15/16ths of income - but it is well known that real hourly wages have stagnated for decades even as the rich have become far richer:

In 2018 the Gini Index stood at 0.485; about where it was after the Wall Street Crash.

It’s hardly surprising that some people indulged in an ambling, bumbling, largely weaponless Capitol ‘insurrection’ on January 6th; under other circumstances, Jefferson would have supported something far bloodier, as he did when observing the French Revolution. However, that was then, this is now.

What would a new Constitution look like? The population is vastly greater and much more economically interconnected than two centuries ago; the means whereby people communicate are largely owned and controlled by a tiny minority; the comprehensive minute spying on everybody is on a scale scarcely imaginable; billions are spent on persuading and misinforming the citizenry. Why should the powers-that-be have any respect for a populace they (barely) sustain and thoroughly manipulate?

So it is that the public have been distracted by politics centering on personal issues rather than systemic ones. The displaced anger and frustration are nevertheless threatening to disturb the established order.

For example, take the furore over the Supreme Court’s redecision on Roe v. Wade. It has led to personal threats for some of the Court’s judges - I’ve seen them termed the ‘black-clad Taliban’ on Facebook - and calls for the abolition of SCOTUS.

Well, now; back we go again to the centrists and decentralisers of the late eighteenth century. Then as now, each party used its powers when in government to poke the other in the eye. When John Adams lost the Presidency in the 1800 election, he tried to hamstring Jefferson’s incoming administration with a rash of last-minute Federalist-supporting appointments to the judiciary; the new President retaliated by withholding the official delivery of the commissions.

This led to the landmark Supreme Court case of Marbury v. Madison in 1803. Adams had nominated William Marbury as a Justice of the Peace in Columbia. Marbury wished the Supreme Court to order the government to deliver his commission, claiming that Section 13 of the Judiciary Act (1789) gave SCOTUS the right to issue such a writ (of mandamus) on its sole authority, without needing to adjudicate an appeal from a lesser court. The Chief Justice ruled that Section 13 was an improper extension of the powers granted to SCOTUS by the Constitution, so that although Marbury was entitled to his commission, the Court was not able to enforce it and Section 13 was struck down as incompatible with the founding document of the Republic. This established the role of SCOTUS as able to revise the law in line with the principles of the Constitution.

For the sake of strong feelings on a particular issue, Americans are urged to smash the system that has been put together so carefully. The implication is that central government should override individual States in response to popular pressure.

Where could this lead?

Imagine that the Federation finally became a single sovereign power, abolishing the 50 Constitutions of its member States. Say that a crowd-pleasing edict reliberalised the abortion laws whose recent devolution to States rules has, some claim, a racially biased effect, proportionally hitting black females more than others.

Let’s set aside the argument that if more black women are affected by this, the real implication is that black people are more economically disadvantaged and that is where the racial inequality really lies.

Consider instead the possibility that some future, financially conservative US government, worried by a welfare state burgeoning out of control, were to make abortion not merely voluntary but mandatory, for unborn children that are likely to be a burden on the public finances: e.g. the disabled, and the poor. If that sounds implausibly Satanic, remember that the writer GB Shaw was advocating this even after WWII, for adults as well as children:

… ungovernables, the ferocious, the conscienceless, the idiots, the self-centered myops and morons.

There would be no fleeing to a neighbouring US State; only emigration could provide escape, assuming the refugees could afford to leave and that another country was willing to accept them.

As Lord Acton wrote in 1887:

Power tends to corrupt and absolute power corrupts absolutely. Great men are almost always bad men, even when they exercise influence and not authority: still more when you superadd the tendency or the certainty of corruption by authority.

Already the power of the US Constitution to constrain the Executive is weakening: see how the President’s ability to make war has been gathered into his own hands without much reference to Congress; how the State is so bloated with tax money and debt that it maintains non-military armies that act almost as though they have carte blanche, that can (it is widely suspected) take it on themselves to subvert their own as well as foreign governments; that historically have persecuted trade unionists as well as dangerous Communists; that have blackmailed the President.

The fantasy that removing one very flawed individual - Trump - will make all well must be exploded. The long-standing and growing tensions within the nation must be addressed through reform of the economy, the political establishment and State agencies, before they burst out into a Jeffersonian civil war.

When the age of cheap energy has passed, perhaps what survives of the nation may indeed revert to an agrarian democratic republic of self-supporting communities. Let’s try, as long as we can, to put off the crisis that will precede that.