Alcohol and the State

In 1911, when California held a referendum on the question of women’s suffrage, the writer Jack London surprised his wife Charmian by saying he had voted in favour, because:

"When the women get the ballot, they will vote for prohibition. It is the wives, and sisters, and mothers, and they only, who will drive the nails into the coffin of John Barleycorn.”

In his 1913 book ‘John Barleycorn’ he claimed that few men were born addicts to alcohol; the real driver was its availability:

It is the accessibility of alcohol that has given me my taste for alcohol. I did not care for it. I used to laugh at it. Yet here I am, at the last, possessed with the drinker's desire. It took twenty years to implant that desire.

Sure enough, the Constitutional amendments introducing Prohibition and granting women’s suffrage were passed within six months of each other, in 1920. Women did not vote directly for Prohibition - there was no referendum, though by 1918 fifteen States had already legalised the female franchise - but the two movements ran in parallel. Women have been ‘blamed’ for Prohibition, though perhaps ‘credited’ is a better term, seeing the practical benefits of the experiment.

London’s accessibility argument is borne out by British history. When the Government deregulated sales of gin in order to turn people away from importing brandy from the enemy, France, the result was an epidemic of drunkenness that forced the passing of the 1751 Gin Act to reduce the damage.

In 1830 there was a second deregulation, of beer houses, to draw people away from spirits; the consequence was another spate of intoxication:

A fortnight after the passage of that Act, Sydney Smith, renowned for his idealism, who, previously, had been a strong advocate of it, wrote: “Everybody is drunk. Those who are not sinking are sprawling. The sovereign people are in a beastly state.”

Since then there have been various episodes of regulatory tightening and re-loosening of licensed hours and premises, from e.g. Sunday pub closures in Wales (1881) to the nationwide availability of 24-hour licenses (2005.)

Outlets have proliferated: today, I would be hard put to count all the places within a mile of our (suburban) house where I can buy alcohol; not just pubs and off-licenses but supermarkets, post offices, garages and convenience stores.

In our post-industrial country, the home is an increasingly important venue for consumption:

The main change in the structure of capital during this century has been the relative stagnation of industrial capital and the growth of the service sector of the economy. This trend, which has been most marked in the south of England, has had consequences for inner city working class areas: de-industrialisation, mobility of labour, and post-war rehousing policies have combined to dislocate the pattern of community based upon local work and extended families and associated cultural traditions...

Population has been decanted to the New Towns, and more generally, to the suburbs, where social life has focussed upon the nuclear family, and the home is increasingly regarded as a place of leisure, recreation and consumption. It is in this context that off-licence sales have become more important. The 1961 Licensing Act relaxed restrictions on the opening of off-licences, and the 1964 Licensing Act facilitated supermarket sales. By the late 1970s, most beer was still sold in public houses, but one third of all wine and half of spirits were consumed at home.

From ‘Alcohol, Youth, and the State’ by Nicholas Dorn (RKP, 1983)

The State is conflicted on the subject: on the one hand there are the health and other costs of alcohol; but on the other there is the fact that the sales taxes represent something like 2% of total Government revenue (not counting the taxes and National Insurance Contributions provided by all those employed in the drinks industry.)

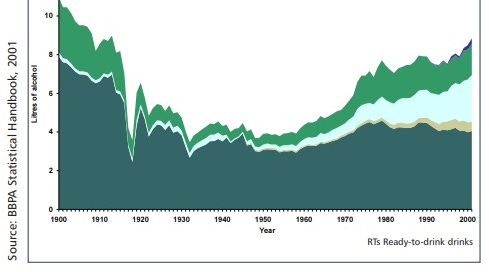

Whether it is to do with the 1961 and 1964 Acts or the general increase in prosperity, there has been a clear (re-)increase in alcohol consumption since the 1950s:

Males drink more than females, though the latter are catching up. On average, men in 2018 were drinking the equivalent of 17.8 litres of pure alcohol per year - in spirits terms, more than five 70-centilitre bottles a month. Bear in mind that around 20% of the adult population doesn’t drink at all (among the young, there may be a switch to drugs instead, especially when beer is retailing at close to £5 a pint in pubs) and according to this survey:

… the very heaviest drinkers – who make just 4% of the population - consume around 30% of all the alcohol sold in the UK.

Even if the State decided to crack down on alcohol abuse, there are powerful commercial interests involved; strong enough to defy the Government, as they did in 1991 over Sunday trading restrictions.

Those who call for further controls over alcohol, tobacco, gambling and drugs will often be accused of ‘nannying’, though the State Nanny is one that has been making it easy for her charges to get the things that harm them, and who gets backhanders from the suppliers; a Satananny, if you will.

Libertarians dislike having anyone say no to them; the line starts behind me on that one, but let’s have no illusions about our supposed complete rationality and freedom of the will: there’s not that many Buddhas in the world. Jack London ended his 1913 book with a personal commitment to a more measured approach to alcohol:

No, I decided; I shall take my drink on occasion. With all the books on my shelves, with all the thoughts of the thinkers shaded by my particular temperament, I decided coolly and deliberately that I should continue to do what I had been trained to want to do. I would drink—but oh, more skilfully, more discreetly, than ever before.

He didn’t live past 40.

We may not get booze and fags back into Pandora’s box, but maybe we can do more about the plague of gambling - so heavily advertised on TV at the moment - and think twice about liberalising drug laws.